What we learned from World War I’s wounded veterans

| 1 March, 2017 | Jennifer Novotny |

Image credit: University of Glasgow Archive Services, Papers of Sir William Macewen, GB248 DC079/173

In one of the first humanities articles published on Wellcome Open Research, Dr Jennifer Novotny from the University of Glasgow describes one of the founding and work of the Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers (now known as the Erskine) during what was then called the Great War. In this guest blog Dr Novotny talks to us about the history of the hospital, what lessons are still relevant today, and her experience of publishing in Wellcome Open Research.

The founding of the Princess Louise Hospital

The Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers (Erskine) was founded in 1916. It was one of many voluntary hospitals established by members of the public to deal with the health crisis of war wounded and disabled during World War I (WWI). In my article, I focus on the vocational rehabilitation and employment of limbless sailors and soldiers, but of course, Erskine’s primary function was as a surgical and limb-fitting facility. The first Chief Surgeon was Sir William Macewen, a prominent medical professional. Prior to Erskine he had developed a strict asceptic procedure to prevent infection, was a pioneer of brain surgery, and methodically researched bone growth and experimented with grafting. Many of the operations (for example, re-amputations) at Erskine were performed by Macewen himself, so patients were getting the very best skilled care.

Public backing for the Erksine

Charitable support for war wounded by members of the British public was necessary, as the government simply could not provide wounded and disabled with the requisite amount of care and support. Charitable donations and volunteerism offered civilians – many of whom probably had friends or family on active service – a way to ‘do their bit’ for the war effort, support those serving, and even commemorate or memorialise lost loved ones.

The endowment of Erskine started with the great and the good of the West of Scotland (industrialists, members of the peerage and civic community who were high profile philanthropists), but it also received grass-roots support from the wider community. The ‘girls’ of the No. 8 Hankwinding Department at the J&P Coats Ferguslie thread works (Paisley) pooled their money for a croquet set while likewise the ‘girls’ working in the Howitzer Department of William Beardmore’s Parkhead (Glasgow) factory got up a collection for a wheelchair. Much farther afield, the British Isles Relief Society of Trenton, New Jersey (USA) offered ‘£20 for the purchase of tobacco and other small comforts’. One of my favourite donations, however, is that from Mrs JS Houston Lang, who offered the hospital a fox terrier, though regrettably that particular gift was declined.

Applying lessons from the programmes at Erskine during WWI to supporting modern disabled veterans

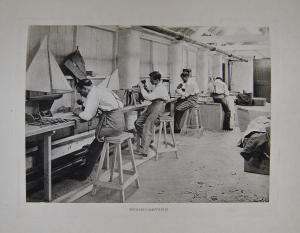

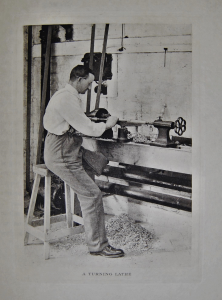

When first started, the Erskine had many workshops that trained veterans in new skills so that they could be productive members of post-war society. The therapeutic benefits, both mental and physical, of work-based tasks like gardening and woodworking are widely recognised and still feature in rehabilitation today. There are also creative new ways to engage in communal rehabilitation. As someone who studies conflict heritage, I particularly admire Operation Nightingale and Waterloo Uncovered, which get injured personnel involved in archaeological excavation. And, of course, the longevity of Erskine itself attests to the continuing need for long-term care for veterans.

For me, studying history offers a way to think about current society. One hundred years on we as a society still struggle to appropriately support service leavers, especially those who join the armed forces at a young age and leave after only a few years. Today there are a number of wonderful national and local charities helping men and women get their lives back on track after injury or adversity. While my article specifically focuses on those made limbless by war, it is important to remember that not all injuries are visible. We remember WWI because of the awful scale of it, but there are ex-service personnel right now in your own community who are struggling, who might be falling through the cracks, despite our 21st-century medical and support programmes.

Why Publish in Wellcome Open Research?

I wanted to publish via Wellcome Open Research for a number of reasons. First and foremost, I believe in open access to scholarly articles. I work at a large Russell Group university and even I don’t have access to all of the articles I would like. Whether we are early career researchers in between posts, independent scholars with no formal institutional affiliations or citizen researchers, curious minds everywhere should be able to access up-to-date research. I also support transparent peer review. Even though it can be daunting to think of your reviewers’ comments being visible to all, it makes the review system more robust and accountable. Another factor in my decision to publish with Wellcome Open Research is that academic publishing often is plagued by lengthy lead-times and other editorial delays. By contrast, my submission to Wellcome Open Research was immediately copy-edited and soon posted for peer review. The time from submission to my first reviewer report was very fast and the experience has been positive.

Cataloguing and conservation of the Erskine archive were funded by the Wellcome Trust. You can view the catalogue here. Contact the University of Glasgow Archives for enquiries or to access the collection.