Haemoglobin is the key – a potential cause of brain atrophy in MS patients

| 14 December, 2016 | Charles Bangham |

Professor Charles Bangham, Head of the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Faculty of Medicine at Imperial College London, recently published an article on the association of free serum haemoglobin with brain atrophy in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis on Wellcome Open Research. In this blog post he summarises the findings, what implications they have for the treatment of the disease and why he decided to publish the article on our platform.

Like many people who have studied clinical medicine I am interested in MS because it is such a mysterious and devastating disease. It’s a lifelong condition that affects the brain and spinal cord, and results in nerves being destroyed. The symptoms, and the severity of the illness, vary widely from person to person: some patients have an episode of blurred vision in one eye in their 20s but never have anything else again. But when you do a brain scan, they have several lesions, whereas other patients might have few lesions but are severely disabled and die early from the disease. No-one knows the cause of MS, or even whether the disease process starts inside the nervous system or outside. At first, patients tend to experience intermittent episodes of the condition, but symptoms improve between each period of illness. However around 65 per cent of patients eventually develop a more severe form of the disease, called secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. In this phase, which generally starts around 15 years after the initial MS diagnosis, the symptoms become steadily worse, with no periods of improvement. One feature of secondary progressive MS is a slow but steady loss of nerve cells in the brain, which causes progressive disability.

Research focus to date

My research has focused on the immunology and virology of persistent viral infections, especially the human leukaemia virus, HTLV-1. As well as causing leukaemia in some people, in others it can cause an inflammatory disease of the nervous system that closely resembles some forms of MS. In the 1980s, a group in the United States published several papers, claiming that the human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) or a related virus was actually the cause of MS. We were some of the first people in the UK doing PCR, and we decided to use the technique to analyse blood samples from MS patients, to see if we could find evidence of the virus. What we found was that the group in the US must have contaminated their PCR reactions. More than 20 different viruses have been suggested to cause MS, even though the evidence that any virus is involved remains very weak and controversial!

I got interested in looking into brain atrophy in secondary MS when Dr Jeremy Chataway contacted me in 2008 to work with him on a project that looked at the effect on the disease of a statin, which we published in the Lancet in 2014.

Our recent findings

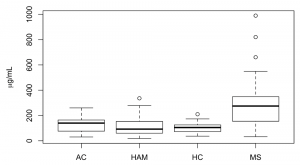

Previous research has found high amounts of iron deposited around blood vessels in the brain. Although the mineral is crucial for our bodies to function, it is toxic in high levels – and scientists have suggested this may trigger the death of brain cells in MS. Building on the findings from our previous collaboration with Dr Chataway, we decided to look for protein biomarkers of brain atrophy in SPMS. In our study of 140 patients with the advanced form of the disease, we found that the brain shrinkage is associated with a leak of a protein out of red blood cells and into the serum. This protein, haemoglobin – whose normal function is to transport oxygen around the body – contains iron, which is found in the brain where the disease is active and is thought to contribute to the nerve damage.

In my opinion, the people currently writing and thinking most carefully about the disease process in MS are Dr Simon Hametner and Prof Hans Lassmann from the Center for Brain Research at the Medical University of Vienna, which is why we asked them to review our article. You can find their report published alongside the article.

What are the implications of these findings?

We were amazed by the results, and we were surprised by the size of the apparent effect of haemoglobin on brain shrinkage. Over a number of years, it could significantly worsen a patient’s symptoms. Some existing trials are testing potential MS treatments that mop up excess free iron, but these treatments might not work well because the iron is tightly held by the protein. Our results suggest that it might be more effective to try treatments that mop up the haemoglobin that has leaked out of the red cells, rather than iron itself. There are number of drugs that do this, although none have been used for multiple sclerosis.

The importance of open data

All our data are available on Zenodo. Making data openly available is important because it allows anyone to check our findings and our analysis, and to use our data in other studies. It also makes it easier for others to test the reproducibility of our results.

Why Wellcome Open Research?

Wellcome Open Research is an exciting new way of publishing scientific results. It is faster and more transparent than publishing in traditional-style scientific journals, it gives more choice to the scientists over what to publish and when, and it also allows credit to be given to people who give good-quality reviews of the work. Reviewers must take great care to give accurate, justified criticism of the research.

I would strongly encourage other Wellcome grant-holders to publish on Wellcome Open Research. I think it has real potential to improve the standard, speed and fairness of scientific publishing.

Professor Charles Bangham is the Head of the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Faculty of Medicine at Imperial College London. After qualifying in medicine and working for three years in hospital medicine, he carried out a PhD on the immune response to respiratory syncytial virus at the National Institute for Medical Research in London and the University of Oxford. In 1995 he was appointed to the Chair of Immunology at Imperial College London.